Introducing flashgeotext: extract city and country names from text

Say you are faced with the problem of extracting the name of a location from a text and count their occurrences. How would you do it in the simplest of manners, if you:

- Have a list of names that you want to extract (10.000+)

- Don’t care about any other name in your text, because you know what you are looking for

- Are on a budget

- Want to optimize for execution time

tl;dr

Go to https://flashgeotext.iwpnd.pw, ignore all that and use it right away.

Let’s brute force it

Let’s brute for this problem and check every word in a lookup against an input text.

lookup = ['Berlin', 'Hamburg', 'London', 'New York', [...]]

input_text = "Berlin is a great city. Berlin is not as nice as Erlangen, but will do for now."

# check if lookup in input_text

isin_text = [city in input_text for city in lookup]

print(isin_text)

>> [True, False, False, True]

Now you know that Berlin and New York are mentioned in the text. But you don’t know how often. So maybe you think of something like:

lookup = ['Berlin', 'Hamburg', 'London', 'New York']

input_text = "Berlin is a great city. Berlin is not as nice as New York, but will do for now."

extract = {}

for city in lookup:

for word in input_text.split():

if word == city:

if city not in extract:

extract[city] = {"count": 1}

else:

extract[city]["count"] = extract[city]["count"] + 1

print(extract)

>> {'Berlin': {'count': 2}}

If your eyes are already bleeding, wipe that away and stick with me some more. Now we have a count for the occurrences of Berlin but are missing New York entirely because we’re iterating over a sequence of unigrams but to match New York we would have to check bigrams of the words in the input text. If we were to look up something like Costa del Sol, it would take trigrams and so on. With some recursive function you might be able to abuse the find() method of Python strings to avoid the use of n-grams, but before we go down that route we cut the conclusion short and say that brute-forcing is not the way to go. At best you’re left with M * N calculations - that is when you’re checking for unigrams. That means every word in the lookup, will be checked against every word of the input text.

What now? Named Entity Extraction!

To reduce the number of calculations and to avoid the use of n-grams, we have to reduce either M (the number of words in the lookup) or reduce N the words in the input text. Reducing M is off the table, because that’s what we’re looking for. Reducing N is something we can do though. Cities, countries, and districts are all named entities. And Named Entities can be extracted, reducing N in the process.

spaCy

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Berlin is an awesome city. It is also great to live in London though.")

for ent in doc.ents:

print(ent.text, ent.start_char, ent.end_char, ent.label_)

>> Berlin 0 6 GPE

>> London 55 61 GPE

spaCy is awesome. It supports a lot of languages. It’s easy to learn, hard to master. It’s super well documented and embedded into a great community and a great ecosystem of plugins/addons/spinoffs. It has a lot of functionality aside from named entity extraction. And it does what it is supposed to do and more. However, named entity extraction with spaCy is still based on a trained model prediction, and even though the core models perform well, they are not 100% accurate. On top of that spaCy is build with C dependencies, which can be a problem in some environments. Also, you are limited to the pre-trained models, unless you want to train your language model from scratch.

Using spaCy limits us to a limited amount of languages that are supported. Locations that are parsed from an input text and returned by spaCy would still need to be checked against a lookup. Slight variations in the input text would drastically change the result.

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Berlin city is awesome. But now imagine you live in London city.")

for ent in doc.ents:

print(ent.text, ent.start_char, ent.end_char, ent.label_)

>> Berlin city 0 11 GPE

>> London city 52 63 GPE

Also, there would have to be a process to calculate the occurrences. Spacys dependencies make it harder (not impossible) to deploy in a low-cost environment such as AWS Lambda.

GeoText

from geotext import GeoText

places = GeoText("London is a great city")

print(places.cities)

>> "London"

GeoText relies on a single regex search pattern to extract named entities from an input text. Afterward, GeoText tries to match every single one of the entities found to a collection of city and country names one by one. This approach is fast for the 22.000 cities that come with the library, but do not scale well with longer texts and more cities/keywords in a lookup file. GeoText also does not make it easy to bring your data. Also, synonyms are not in the scope of GeoText. Another problem is the regex search pattern that extracts named entities. It is a fine line between matching correctly and matching too much, and it gets even harder to match when city names contain more than a couple of words. Have fun matching something like Friendly Village of Crooked Creek.

Nonetheless, GeoText comes very close to what I had in mind. GeoText provides named entity recognition, even though it has its flaws. It provides some sample data from Geonames that can work as a lookup. It is a native python implementation and will run anywhere. Where GeoText struggles is that it comes batteries included but doesn’t provide you an opening to bring your data. Also, the regex statement has its limits.

Conclusion

By extracting named entities we reduce the number of computations necessary to look up keywords in a text tremendously. However reducing the number of computations is of no great use, if we can’t match the lookup against the extracted entities. Spacy is a great framework, but not the tool for the job. GeoText looks like the tool for the job but is flawed when it comes to entity extraction and flexibility.

Aaand now?

What if instead of reducing N the number of words in the text to check against a lookup explicitly? What if we would be able to go over the input text, character by character, in one go and would only perform an action if the character is

a) the start of a word, ergo follows a non-word character and

b) the character is even present in our list of keywords to lookup?

FlashText an Aho-Corasick implementation

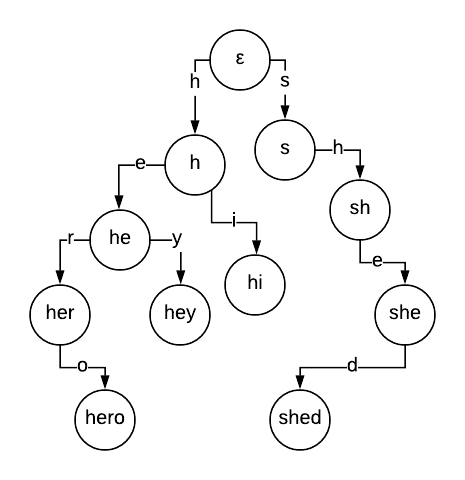

FlashText (see paper) is loosely based on the Aho-Corasick Algorithm used in string-searching. Using the keywords in the lookup data a Trie dictionary is built. The tree is grown by adding edges down from node to node where edges are comprised of letters in each of the strings being added.

source: banay.me

source: banay.me

This allows it to iterate over the input text character by character, and only if the character matches the trie dictionary from start to finish a match is found and stored separately.

from flashtext import KeywordProcessor

lookup = ['Berlin', 'Hamburg', 'London', 'New York']

input_text = "Berlin is a great city. Berlin is not as nice as New York, but will do for now."

processor = KeywordProcessor(case_sensitive=True)

processor.add_keywords_from_list(lookup)

processor.extract_keywords(input_text, span_info=True)

>> [('Berlin', 0, 6), ('Berlin', 24, 30), ('New York', 49, 57)]

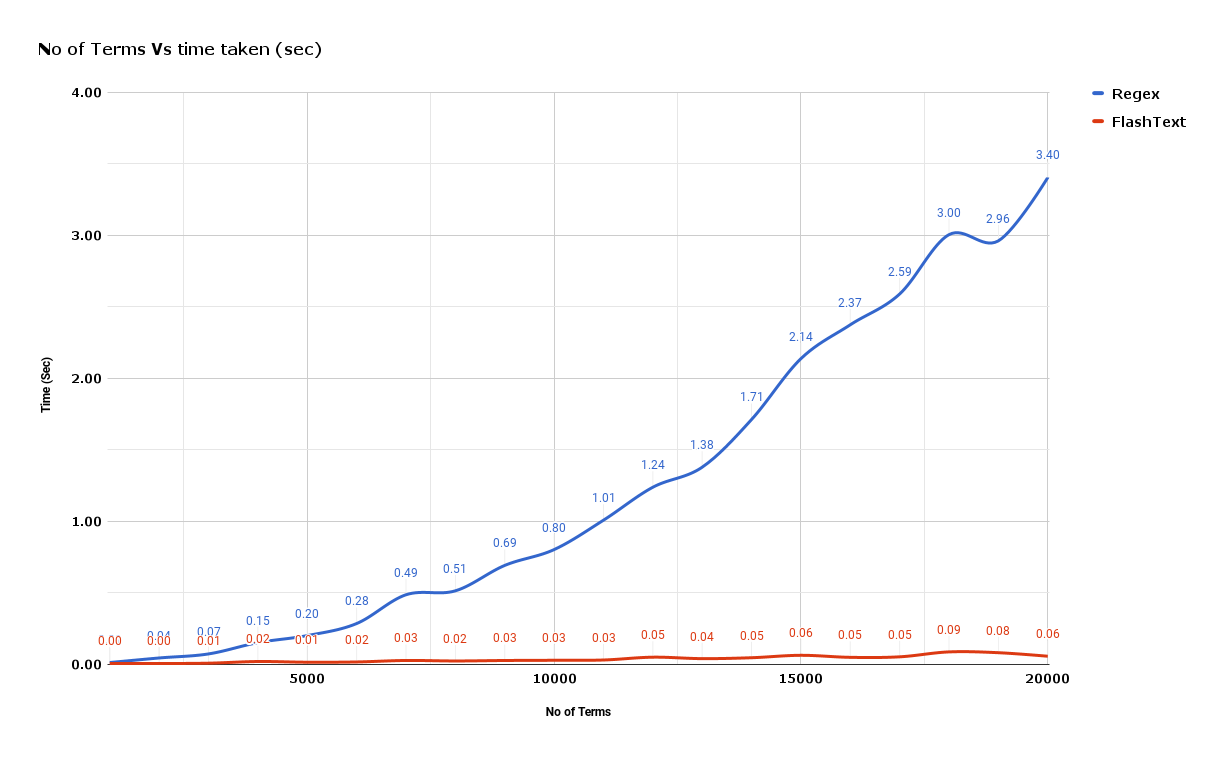

This makes FlashText super fast compared to other approaches.

source: github.com/vi3k6i5/flashtext/

source: github.com/vi3k6i5/flashtext/

Flashgeotext

flashgeotext is my approach in making something good like FlashText, even better by adding some quality of life add-ons to it. It is also intended as a homage to GeoText following a discussion late last year.

Features

batteries included lookup

flashgeotext comes with batteries included. Just like GeoText, you can add city names from geonames.org as a lookup by default and start going right away.

from flashgeotext.geotext import GeoText

geotext = GeoText(use_demo_data=True)

input_text = '''Shanghai. The Chinese Ministry of Finance in Shanghai said that China plans

to cut tariffs on $75 billion worth of goods that the country

imports from the US. Washington welcomes the decision.'''

geotext.extract(input_text=input_text, span_info=True)

>> {

'cities': {

'Shanghai': {

'count': 2,

'span_info': [(0, 8), (45, 53)]

},

'Washington, D.C.': {

'count': 1,

'span_info': [(175, 185)]

}

},

'countries': {

'China': {

'count': 1,

'span_info': [(64, 69)]

},

'United States': {

'count': 1,

'span_info': [(171, 173)]

}

}

}

improved data handling

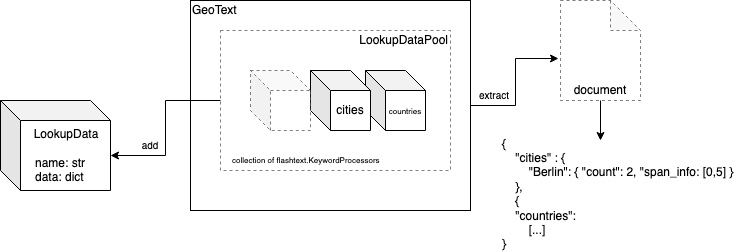

The idea is to provide a way to add additional data to the already provided data from Geonames or use your data for the lookup entirely. This is achieved by utilizing a quasi composite pattern. You instantiate LookupData with your data (see example) and add that instance to a LookupDataPool, which is just a collection of flashtext.KeywordProcessor’s. On extract() for every LookupData in the pool there is one passing and extraction over the text, which amounts to the complexity of O(N * number of LookupData). The extracted data is parsed, occurrences are counted, and span information stored and returned.

small footprint and no dependencies

Just like FlashText, flashgeotext does not have any big dependencies which make it easy to use in AWS Lambda and/or AWS Step functions. Once instantiated on a warm AWS Lambda/Stepfunction, it can be reused again and again. You can easily put every city name on earth into a trie dictionary and run it inside an AWS Lambda’s 3072mb of memory.

non-word-boundaries

FlashText’s non-word boundaries that are essential in during keyword extraction are comprised of

non_word_boundaries = set(string.digits + string.ascii_letters + '_')

print(non_word_boundaries)

>> {'k', '6', 's', 'M', 'i', 'S', 'm', 'E', 'r', 'W', 'v', 'l',

'R', 'f', 'e', 'X', '7', '3', 'q', 'w', '0', 'x', 'V', 'C', 'n',

'I', '4', 'D', 'z', 'G', 'L', '2', 'T', 'U', '_', 'B', 't', 'Q',

'd', '9', 'h', 'o', 'c', 'u', 'P', 'K', 'Y', 'p', 'A', 'J', 'O',

'N', 'H', 'j', 'a', 'Z', '5', '1', 'b', 'y', 'F', '8', 'g'}

This has been are-occurring issue in the past. The fact that there are a lot of characters missing, makes it, that FlashText is unreliable at best for every other language than English. I’m currently working on handling different alphabets within flashgeotext to make it possible to reliably extract keywords from a text written in Cyrillic or Greek characters also.

Conclusion

Flashgeotext can help you to extract city and country names in your text processing pipelines. It gives you the ability to add your data instead of or on top of the demo data provided. It is incredibly fast, reliable, written in native Python and easy to set up in an AWS Lambda/Stepfunction environment or as Airflow / Luigi / Prefect directed acyclic graph.